In September, 2019, the Primary Industries and Regions Agency of South Australia (PIRSA) announced a three-year ban on fishing for Snapper, the state’s iconic fish species. The decision came after a recent stock assessment revealed that, in the last five years, Snapper stocks had become alarmingly endangered.

Banning Snapper fishing caused quite a stir among local commercial fishers and charter guides.

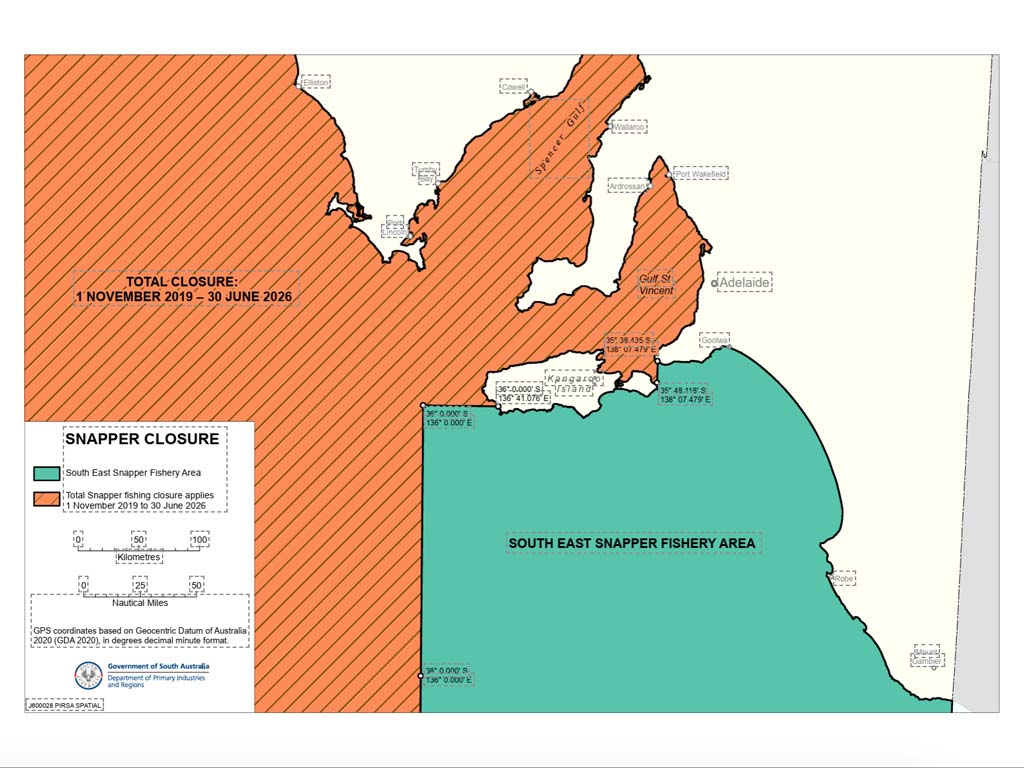

In action since November 2019, the ban completely outlawed fishing for Snapper on the West Coast, in Spencer Gulf, and Gulf St. Vincent. In the state’s South East region, a seasonal ban was set to prevent fishers from targeting Snapper from November to February, each year, though it was eventually lifted.

Fishing for Snapper is a big deal in South Australia. For years, the prospect of catching this fish had anglers flocking to its coasts. As a prized delicacy, Snapper was a tremendous asset for the commercial fishery, as well. According to PIRSA, this fish alone was bringing an annual $5.2 million to South Australia.

The Snapper, however, was being loved into extinction. Over the last four years, Snapper populations in Spencer Gulf have dropped by 23%. In the Gulf of St. Vincent, they plummeted by a whopping 87%! Needless to say, the species had come into grave danger.

The findings, originally published by the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), showed that if not regulated, Snapper fishing could inevitably wipe out the iconic fish altogether. With this unsettling thought in mind, PIRSA officials decided to close the fishery down.

Of course, local fishers knew that Snappers weren’t as abundant as they once were. In fact, they were the first ones to notice their decline. To most of them, the change in regulation didn’t come as much of a surprise. What was surprising, however, was how radical the change was.

Snapper fishing was banned for seven years. That’s a long time, especially for a local ‘mom and pop’ business dependent on the Snapper bite to put food on the table. Restaurants and fishing guides, tackle shops, and retailers were all about to take a big hit.

A Word on Snapper

Before we get into what the Snapper ban means for South Australia, let’s take a closer look at what makes this fish so special.

Snapper, aka Silver Seabream, are widely distributed coastal fish native to Australia, New Zealand, and Japan. These are long-living fish, capable of reaching 40 years of age throughout their range. Snapper can get decently large, too. Spawning males often reach 130 centimeters (50 inches) and 20 kilograms (44 pounds). Most commonly however, Snapper range between 5 and 10 kilos (11–22 pounds).

Depending on how old they are, Snappers go by different names. Juvenile Snappers are called cocknies. Riggers is the name for smaller keepers, whereas the fully grown Snappers are known as squirefish. You can recognize these larger males by the distinct bony hump on their forehead.

As food, Snapper are one of the most coveted fish in all of Australia. Their lean, white meat boasts a delicious, mildly sweet flavour. They’re easy to cook, and can be prepared in a wide variety of dishes. Seafood restaurants throughout Australia offer Snapper as one of their prime delicacies.

Snapper inhabit a wide range of habitats, ranging from coastal estuaries, to reefs, and edges of the continental shelf. In South Australia, they live as three separate stocks. These are the Western Victorian (shared with Victoria), the Spencer Gulf, and the Gulf St. Vincent stocks.

The three stocks may be relatively close to one another, but in terms of sheer abundance, they couldn’t be further apart.

The Numbers

To complete the stock assessments, SARDI scientists used two data-gathering methods. The first, a ‘fishery-dependent’ method, included monitoring commercial fishing statistics, such as longline and handline catches. To get an even better picture of the Snapper stock, the scientists also monitored the age at which the fish were caught.

As for the ‘fishery-independent’ data, the scientists looked at a measure called DEPM (daily egg production method) to determine the Snapper spawning biomass. Knowing the fecundity (the ability to produce eggs) of Snapper, the DEPM showed scientists exactly how large the spawning populations of Snapper actually were.

This is what they found.

Gulf St. Vincent

In 2014, the Gulf St. Vincent Snapper spawning biomass totaled 2,590 metric tons. Over the next four years, the number plummeted to 343 tonnes. That meant that the Snapper population had dropped by 87%! Looking at this figure alone, one could argue that the Snappers simply relocated to another spawning ground. However, combining the biomass data with the commercial catch information painted an eerily different picture.

In 2014, commercial fishers caught 389 tonnes of Snapper in Gulf St. Vincent. In 2018, they only managed to catch 157 tonnes. Combined, the two stats undeniably showed that the Snapper population was decreasing. With this new information in hand, SARDI officially flagged the Gulf St Vincent Snapper stock as ‘depleting‘.

Spencer Gulf

Meanwhile, the 2013 Spencer Gulf Snapper spawning biomass equaled around 236 tonnes. Six years later, the spawning Snappers dwindled to just 192 tonnes. That was a 23% reduction. The numbers perhaps weren’t as dramatic as in Gulf St. Vincent, but they were worrisome all the same.

The commercial catch in Spencer Gulf was traditionally cyclical, with peaks in 1990, 2001, and 2007. However, since the 2007 catch, which equated 616 tonnes, commercial fishers saw a sudden drop in their catch totals. For the last 10 years, the annual commercial catches in Spencer Gulf barely broke the 70 t mark.

Considering that the commercial catch had been low for more than a decade, and that the overall population had decreased, SARDI flagged the Spencer Gulf Snapper population as ‘depleted‘.

South East Region (Western Victorian Stock)

The Snappers of the South East region belong to a larger Western Victorian Snapper (WVS) stock. This regional population owes its numbers to the seasonal migrations of Snappers born in Port Phillip Bay, Victoria. Over the last decade, these Snappers were able to reproduce at a very high rate compared to the other two Snapper stocks.

But that’s not all. South East Region fishery traditionally produced small catches. In the last five years, commercial fishermen only took an average of 20 tonnes of Snapper per season. With good numbers of juvenile Snappers, and low fishing pressure, the fishery was in good shape.

As a result, the WVS Snappers are classified as ‘sustainable’.

The overall picture wasn’t good. Out of the three South Australian Snapper fisheries, two seemed to be heading to a very steep cliff. The fisheries were ‘screaming’ for a solution.

The Regulations

The SARDI research didn’t just show that the Snapper stocks were in trouble. It also pointed out how dramatically a fish population can change in just five years. Regulators thought that the only way to reverse the trend was to put forward a solution that was equally as dramatic.

In August 2019, PIRSA opened up two regulation proposals for public consultation. After reviewing close to 900 submissions from local commercial, charter, and recreational fishing groups, PIRSA drafted the new rules.

By September, the new South Australia Snapper fishing regulations were official:

- From 1 November 2019 to 30 June 2026, Snapper fishing is banned in the West Coast, Spencer Gulf, and Gulf St. Vincent regions.

- During the closures, catch-and-release fishing is strictly forbidden. A $315 on-the-spot fine or, if prosecuted, a maximum penalty of $20,000 may apply.

- Snapper fishing is allowed in the South East region with a 2-fish personal daily bag and a 6-fish boat limit.

- A total allowable catch (TAC) will be set and shared between the commercial, recreational, and charter fishing sectors. If the TAC is reached, the fishery will be closed.

A Tough Pill to Swallow

As expected, the new regulations caused a huge wave of discontent from local fishing associations. Across the Yorke and Eyre peninsulas, people were voicing their frustration. And who could blame them: their primary source of income was about to become off limits. It wasn’t just the anglers, either. Seafood processors, retailers and consumers, restaurants, and bait-and-tackle shop owners – the list of unhappy individuals and organizations went on and on.

Coastal Australia’s local councils did agree that Snapper populations needed stricter rules. However, they were also disgruntled with the neglect of the economic problems the new regulations would cause.

One of the opposing local councils was the Yorke Peninsula Council. While agreeing that Snapper populations needed tighter regulation, the council felt like the proposed solutions would have devastating consequences to local tourism. They and many others recommended a shorter closure, a reduction in bag limit, or a longer seasonal closure in specific areas.

Seafood retailers, like the Angelakis Bros. have said that they will now need to look to import Snapper from places like Western Australia, Victoria, and even New Zealand. According to people in the tourism industry, there’s no telling what importing Snapper will do to South Australia’s reputation as a prime seafood destination. More importantly, however, importing Snapper will likely cause its prices to skyrocket.

And then there are those who distrust the new Snapper findings completely. Many commercial fishers and charter guides contend that the recent findings are incorrect, and that they’re only taking the last 10 years of Snapper data into account. These fishermen claim that, prior to 2010, Snapper fishing was pretty much on the same baseline as it is today. For this reason, they are pretty much unanimous in their requests for more research.

Easing the Pain

Under the 2007 Fisheries Management Act, PIRSA had the authority to give conservation efforts full precedence over social and economic impacts. Thankfully, they realised that the new regulations would create dramatic consequences, both socially and economically.

According to Sean Sloan, Executive Director at PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture, the agency has already introduced a wide range of support and education measures for those impacted by the Snapper closures.

‘These measures include a 50% reduction to the Marine Scalefish Fishery licence fees, which will be at a cost of $3 million.’

And while a 50% discount on licence fees will certainly help commercial fishers, it doesn’t really solve the issue of how charter fishing guides will get any bookings. To that end, the government will help introduce several additional measures.

Mr. Sloan explains, ‘We’re conscious that the restrictions will impact the charter fishing industry. For this reason, The Regional Growth Fund will provide a $500,000 grant scheme so that Charter boat Fishery licence holders can improve their businesses and tourism offer.’

Under the grant scheme, local charter operators will be able to seek grants anywhere from $2,000 up to $25,000. There will be a minimum 50:50 project funding contribution requirement. Charter operators will be able to apply for projects such as:

- Improvements to boat amenities (e.g. fridge, catering equipment, seating)

- Improvements in boat accessibility (e.g. disability, elderly)

- Marketing, promotions, and booking management systems

- To purchase equipment that will deliver new customer experiences

- Upgrade of boat survey and associated boat alterations

- Boat alterations to support tag-and-release science work

- Boat alterations to support new customer experiences

- Business strategies to plan for diversification

A Light at the End of the Tunnel

As bad as things seemed when PIRSA first announced the closures, hearing about all the support measures brought some much needed hope to South Australia’s commercial and charter fishers. However, all the hope in the world would mean little if seafood consumers and recreational anglers weren’t willing to make a big shift.

Shifting Focus

The majority of South Australia’s recreational anglers come from out of state. With their favourite species now off the table, they might look to cast their lines elsewhere. Or they could choose to shift their entire focus to another fish. The question is, how to keep anglers fishing, while avoiding the same scenario for another species?

The answer, according to science, lies in diversification.

Based on earlier SARDI stock assessments, South Australian fishers have traditionally focused on a few select species. Apart from Snapper, these included King George Whiting, Garfish, and Southern Calamari.

The thing is, South Australia is so abundant with fish, that recreational fishers and consumers don’t really need to have such a narrow focus. There’s so much more to catch in these waters.

Captain John Tiller aboard Keen As Fish, SA Fishing Charters in Marion Bay, agrees: ‘I think that, instead of turning people off from fishing in our state, we should focus on all the other species on offer in South Australia.’

Captain John is hopeful that people will still come to South Australia to fish. An offshore specialist, John will continue to target species like Kingfish, Samson fish, Tuna, and Sharks.

For anglers who don’t necessarily want to fish offshore, South Australia still has plenty of alternatives to offer. According to PIRSA, the best choices include: Snook, Sweep, Australian Herring (Tommies), Leatherjackets, Yellowtail, and Western Australian Salmon.

Lastly, in the South East region, where Snapper fishing will still be seasonally available, PIRSA will be introducing educational materials with local fishing organizations and tourist offices. The Recreational Fishing Guide App will get a revamp, so that anglers can access all the education materials online. The app will also feature the latest weather and regulation updates.

The Outlook

The South Australian Snapper ban will likely completely change the face of fishing in the state. Over the next three years, recreational anglers, commercial fishers, and charter guides will all need to drastically change the way they catch fish. Seafood consumers, hotels, and restaurants will also need to adapt to the new rules.

The shift won’t be an easy one, especially for small businesses that depended on Snapper to make a profit. Thankfully, South Australia is uniquely suited for such a change. With waters abundant in a myriad of other species, and no shortage of willing anglers, fishing will be able to thrive.

If there’s one thing we know, it’s that a fishery can change a lot in a few years. Let’s hope that this time, the change is a positive one.

What are your thoughts on the South Australia Snapper ban? Do you think that closing the fishery down for three years was a good idea? Let us know in the comments below.